Concept Note

The Government of India has enacted several policies to foster long-term sustainable growth, while meeting its short- and long-term commitments to mitigate climate change. This workshop aims to foster debate among academics, policymakers and practitioners on the appropriate policies to meet the stated climate targets.

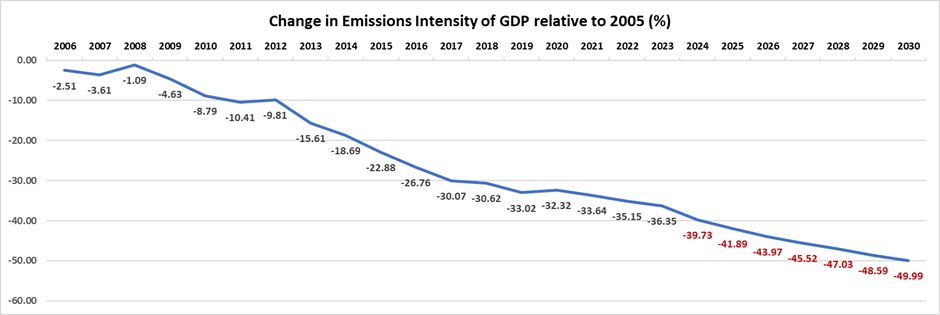

One of India’s Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) is a reduction of the emissions intensity of GDP from its 2005 level by 45% by 2030. A linear extrapolation of the trend between 2005 and 2023 suggests that the country is likely to meet this target three years ahead of schedule and possibly even achieve a 50% reduction from the 2005 level by 2030 as seen in the figure below.

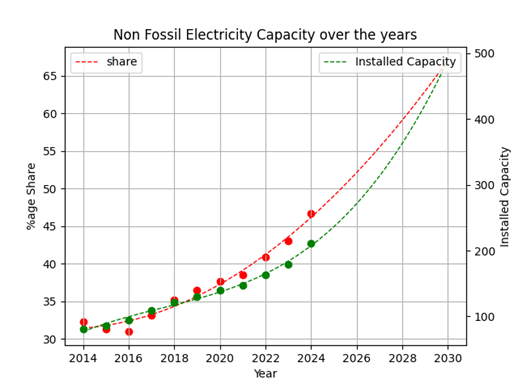

A second NDC is for 50% of India’s electric generating capacity to come from sources other than fossil fuels by 2030. As seen in the figure below, this target is very likely to be met. At the Conference of the Parties to the UNFCCC in 2021, the Prime Minister had also announced a target of 500 GW of non-fossil-fuel electric generating capacity to be installed by 2030. As seen in the figure below, extrapolating the past growth, even this more ambitious target appears to be within reach, although it will require rapid growth in non-fossil capacity.

The targets described above are near-term goals. A long-term NDC is for India to have net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2070. At the same time, however, long-term sustainable economic growth is vital for India to eradicate poverty and enable social mobility. The NITI Aayog estimates that India will need to sustain an annual real per capita income growth rate of 6% to achieve the Government of India’s vision for a Viksit Bharat (developed India) by 2047.[1]

2047 is halfway to 2070. If emissions are to reach near zero by 2070, this suggests that they should peak by about 2047. If the economy is growing at 6%, then for emissions to reach a zero growth rate, then by that year, emissions intensity will have to be declining at an annual rate of 6%, and the rate of decline in emissions intensity will have to exceed the growth rate of income thereafter. Looking back, we see that emissions intensity has declined at an annual average rate of only 2.6% in the last 20 years. Meeting the net zero target while at the same time achieving prosperity remains a challenge.

Forward-looking policies are needed to meet this challenge.

The Ministry of Power has notified the Carbon Credit Trading Scheme, which mandates firms to reduce their carbon dioxide emissions per unit of output and allows trading of carbon credits among firms to ensure firms comply with the requisite standards.[2] The Voluntary Carbon Markets scheme is also being discussed as an initiative to promote afforestation, within India’s Long-Term Strategy for Low-Carbon Development (LT-LEDS), which the Government of India submitted to the UNFCCC in 2022.[3]

Research can be informative for policy design. Economy-wide carbon pricing and emissions trading schemes could enable markets to redirect investments towards clean energy, as in the case of the European Union and China.[4] However, carbon prices may impose short-run costs on social welfare. International finance could greatly help to mitigate these short-term costs from carbon pricing and other mitigation policies in low- and middle-income countries.[5] How can appropriate policies be designed to enable low-carbon growth while reducing emissions, in a socially equitable way?

[1] NITI Aayog. (2024). Viksit Bharat: Unshackling Job Creators, empowering growth drivers. Govt. of India.

[2] Ministry of Power. (2024). Detailed Procedure for Compliance Mechanism under CCTS. Govt. of India.

[3] Ministry of Environment, Forests and Climate Change. (2022). India’s Long-Term Low-Carbon Development Strategy. Govt. of India. Submitted to the UNFCCC.

[4] Dechezleprêtre, A. et al. (2023). The joint impact of the European Union emissions trading system on carbon emissions and economic performance. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 118, 102758.

Goulder, L. et al. (2022). China’s unconventional nationwide CO2 emissions trading system: Cost-effectiveness and distributional impacts. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 111, 102561.

[5] Soergel, B. et al. (2021). Combining ambitious climate policies with efforts to eradicate poverty. Nat Commun 12, 2342.